Good but creepily flawed

Ever since I read Donald Kingsbury’s Psychohistorical Crisis I have been recommending it every chance I get. At a little over 700 pages (in my edition), this book has not been high on my list of rereads, but as I’m waiting for R. Scott Bakker’s Unholy Consult to come out in July (2014) and I’m not in the mood to start anything new at the moment, I decided to pull it out of storage and see if it holds up.

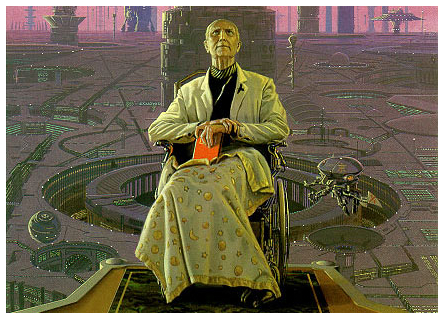

The book is a quasi-sequel to Asimov’s classic Foundation series. Kingsbury (as I understand it) had difficulties securing the rights to use Asimov’s work so he approached things indirectly. For example, “Terminus” becomes “Faraway” and “Trantor” is now “Splendid Wisdom.” The Mule, the psychic mutant from Foundation and Empire, is “Cloun-the-Stubborn,” his mutation morphing into a technological device (the ancestor of the quantronic familiar, about which more below), and the world from which he defeats the Foundation is “Lakgan” (sted “Kalgan”). Hari Seldon is never mentioned; instead, the man who invented psychohistory is always referred to simply as “The Founder.”

The story is set about a thousand years after the Pscholars of the Second Foundation have united the galaxy under the second Galactic Empire. Using the mathematics of psychohistory, these men (and I’ll elaborate upon that deliberate use of the gendered word below) have maintained peace and prosperity throughout the galaxy, and seem poised to continue to do so indefinitely. However, a young, brilliant Pscholar – Eron Osa – believes he has discovered evidence that, despite appearances, the empire is in the midst of a Seldon Crisis. Jars Hanis, the Rector of the Lyceum and the highest ranked Pscholar, panics and has Eron’s fam destroyed, effectively executing him. Fams – quantronic familiars – are the descendants of Cloun-the-Stubborn’s mind-control device. They are symbiotic machines that greatly expand the human mind’s (the wetware) capacity to think and process information. Every citizen of the empire – nearly every citizen – gets one when he or she is three. Human brain and fam develop and mature together. To destroy one, is to effectively destroy the other.

Those parts of the book set in the present deal with the suddenly merely human Eron’s efforts to survive without a fam and to try and discover what he had done to be punished so severely. The majority of the book, however, deals with the years leading up to Eron’s fall, when he was subtly manipulated by a cabal of renegade psychohistorians (the Oversee) into wanting to be a Pscholar; his entrée into the Lyceum; and being taken under the wing of the second-ranked Pscholar, Hahukum Konn, Hanis’ bête noire.

The novel’s finale pits the established psychohistorical model of the empire against Eron’s predictions.

Having digested Psychohistorical Crisis again, I can still recommend it, though not as enthusiastically as before. If you have any interest or liking for Asimov’s original novels (the first three, at least), seeing what Kingsbury does with the universe is fun, and he does his best to make the “science” of psychohistory plausible. Of course, the romance has faded and I can see flaws in the story telling. The author’s primary sin? Too much of the book is taken up with back story. The ending feels rushed and incomplete.

The second flaw is that there are no serious female characters. At all. This may be a nod to the era in which the original books were written, when fully realized females were few and far between in most SF novels. If so – it’s not readily apparent. For example, apparently there are no female psychohistorians. All of the ones we meet are men; and even in references to past Pscholars none appear to have been women. It’s as if Barbie’s famous comment, “Math is hard,” has been taken seriously. And of the women who do appear, they’re either housemaids (e.g., Magda) or mostly interested in sex with our hero or some other male character (e.g., the nameless captain of a starship).

There is one woman, Nemia, an agent of the Oversee, who exhibits talents outside of the bedroom. She’s a master technician, and a genius at fiddling with fams. But even in the Oversee, “math is still hard,” as it’s her grandfather who’s the psychohistorian.

The third flaw is also gender related. Most of the women in this book are underage girls, and there’s a strong flavor of paedophilia throughout the novel. This I can’t forgive as a sideways homage to ‘50s SF, and is my strongest reservation about recommending this to anyone. It reflects a trend I’ve noticed in a lot of the hard SF I’ve read, esp. from older authors – a fixation on certain things, including extended lifespans and having sex with young women (e.g., Peter Hamilton in Pandora's Star and Judas Unchained, though he doesn’t go quite so far as to descend to paedophilia. Larry Niven in Lucifer’s Hammer and Glen Cook in The Silver Spike and most recently in A Path to Coldness of Heart, both of whom have paedophile characters who are not “bad guys.” Perhaps I don’t read widely enough in this particular part of the field. And thereare authors in this genre I really like – Alastair Reynolds or Michael Flynn, to name two, but these others are big-name authors, not minor talents or self-published.

Having written the above, should I continue to recommend this book? With some trepidation, I would say, “yes,” but I would now add the caveat that there are some distressing flaws in the novel that may ruin the reader’s enjoyment of what is good.