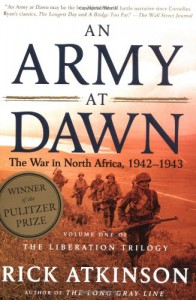

I started Atkinson’s Liberation Trilogy with his second book - The Day of Battle - but that was such an informative and well written account of the Italian campaign that when I came across a copy of An Army at Dawn in a local used bookstore, I picked it up immediately.

I started Atkinson’s Liberation Trilogy with his second book - The Day of Battle - but that was such an informative and well written account of the Italian campaign that when I came across a copy of An Army at Dawn in a local used bookstore, I picked it up immediately.Overall, I wasn’t disappointed.

Despite the occasionally overwrought prose (which I don’t remember so much from The Day of Battle), Atkinson manages to relate the invasion of North Africa and the subsequent campaign to take Tunis with bracing clarity and drama. The careless reader might get lost in the forest of names and fast-breaking events but that’s why God invented indices and cartography – both resources with which this book are amply equipped.

Atkinson is not a historian and the chief theme underlying his story is that North Africa was the crucible that forged an effective Allied army and made or broke the careers of the men who would lead it, particularly Eisenhower. Somehow Eisenhower’s superiors saw something in the relatively young, untried officer and promoted him over a number of senior officers. These qualities were well hidden, however, in the initial stages of the African campaign. Ike didn’t have any experience commanding an army and he was a tyro in dealing with the delicate egos of politicians and generals. As a consequence, the battles were ill planned and stalled with the coming of winter in 1942. It also meant that incompetent commanders were left in command for far too long, with disastrous results for the men they led. The “poster boy” of this contingent was the general of the II Corps, Lloyd Fredendall, whose cowardice and incompetence finally forced Eisenhower to cashier him but only after thousands had paid the price.

From my readings in WW2 history (admittedly not as extensive as they could be), I would tend to agree with Atkinson’s point. If the Allies had invaded northern Europe in 1943 as Roosevelt and Churchill contemplated, it would have been an unmitigated disaster. We may still have won eventually but it would have taken a measure of political will that probably would have been absent without victories to bolster morale; and it would have been devastating to military confidence.

Beyond that, there were several events/themes that stood out to me:

(1) It’s a little advertised fact that the first troops we engaged in battle were Vichy French. I suppose this sticks in my mind only as in illustration of the complexities of reality. The Allies were never of one mind about the course of the war and its aftermath, and the French were not just waiting for their Allied friends to arrive so that they could through in with them.

Another illustration of this was Roosevelt’s assertion of “unconditional surrender” at the Casablanca conference. A move that surprised and chagrined Churchill, who had discussed the idea with the Americans but certainly hadn’t committed himself.

(2) On the whole, the Germans were simply better at fighting a war. This doesn’t mean their commands weren’t riven by political and personal animosities or that incompetence didn’t rear its ugly head – they were and it did - but the commanders were more professional, the men better trained, the commands better integrated (the Germans tended to ignore their Vichy and Italian allies in planning campaigns, and not without cause), and German logistics better coordinated (the Germans did more with far less than the Allies). It’s a frightening prospect to imagine an Axis that had access to the materiel wealth that the Allies eventually enjoyed.

(3) Which brings us to my third point: the overwhelming materiel superiority of the Allies. They could afford to make mistakes. Several, in fact. Atkinson quotes an unnamed general as saying, “The American Army does not solve its problems, it overwhelms them.” (p. 145) From February to March 1943, 130 ships sailed to Africa with 84,000 troops, 24,000 vehicles and a million tons of cargo. The Germans were fortunate to slip a handful of ships across the straits from Sicily against Allied bombing.

(4) For me, the most interesting part of the book was finding out about the Allied commanders – who they were, their personalities and how they coped with the realities of battle (a new experience even for the WW1 vets as technology had made the Second World War and entirely new way of fighting). I’ve already mentioned Eisenhower and Fredendall but we meet any number of lower ranking officers of varying qualities and competencies, including George Patton, the icon of the can-do, hard-charging American soldier. My feelings of loathing for this borderline psychopath were only reinforced despite Atkinson’s generally admiring treatment. One of Atkinson’s strengths, though, is his evenhanded treatment of the subject – no commander is perfect and all made some truly egregious errors that cost tens of thousands of lives. The better learned from their mistakes; the best also realized the human cost of their folly.

Atkinson’s breakdown of the problems of command is a salutary antidote against the armchair generals who look back at Kasserine Pass and other battles and say, “Well, if only they had done this,” or ask, “Why didn’t he throw X brigade into the line at this point?” It’s surprising how little information planners had on hand, who yet confidently drew up ambitious battle plans. What’s even more surprising is how often the Army managed to pull them off, regardless.

I would definitely recommend this book as well as The Day of Battle to anyone interested in military and/or WW2 history, and I look forward to the third installment, which promises to deal with the D-Day invasion and its aftermath.