Titus Groan: Part 1 of 3:

Titus Groan: Part 1 of 3:Peake’s writing in this first Gormenghast novel reminds me of E.R. Eddison’s in The Worm Ouroboros, both for its fecundity and for the manifest enjoyment in the English language its author feels. Twenty years ago – even as few as 10 – I wouldn’t have appreciated this book and would have stopped reading it rather quickly but today I can’t help but thrill to opening passages like:

This tower, patched unevenly with black ivy, arose like a mutilated finger from among the fists of knuckled masonry and pointed blasphemously at heaven. At night the owls made of it an echoing throat; by day it stood voiceless and cast its long shadow. (p. 9)

Or to the vivid descriptions that pepper the narrative:

It was a long head.

It was a wedge, a sliver, a grotesque slice in which it seemed the features had been forced to stake their claims, and it appeared that they had done so in a great hurry and with no attempt to form any kind of symmetrical pattern for their mutual advantage. The nose had evidently been the first upon the scene and had spread itself down the entire length of the wedge, beginning among the grey stubble of the hair and ending among the grey stubble of the beard, and spreading on both sides with a ruthless disregard for the eyes and mouth which found precarious purchase. The mouth was forced by the lie of the terrain left to it, to slant at an angle which gave to its right-hand side an expression of grim amusement and to its left, which dipped downward across the chin, a remorseless twist. It was forced by not only the unfriendly monopoly of the nose, but also by the tapering character of the head to be a short mouth; but it was obvious by its very nature that, under normal conditions, it would have covered twice the area. The eyes in whose expression might be read the unending grudge they bore against the nose were as small as marbles and peered out between the grey grass of the hair. (p. 107)

Based on the first book, we’re swimming in three- to four-star territory.

Gormenghast: Part 2 of 3

There is a scene early in Gormenghast where Titus is immured in the Lichen Fort for playing the truant and he is visited on his last day by Professor Bellgrove and Dr. Prunesquallor, and all three wind up playing marbles:

For the next hour, the old prison warder, peering through a keyhole the size of a table-spoon, in the inner door, was astounded to see the three figures crawling to and fro across the floor of the prison fort, to hear the high trill of the Doctor develop and strengthen into the cry of a hyena, the deep and wavering voice of the Professor bell forth like an old and happy hound, as his inhibitions waned, and the shrill cries of the child reverberate about the room, splintering like glass on the stone walls while the marbles crashed against one another, spun in their tracks, lodged shuddering in their squares, or skimmed the prison floor like shooting stars. (p. 522)

I wish I could reprint the entire episode as it’s brilliant and magical and is an example of Peake’s ability to meticulously set up a scene for maximum effect. And there are many more I could bring up. In Titus Groan, Flay learns something from his exile and his witness to Keda’s suicide (pp. 345-50). Peake lovingly lingers for 30 pages building up to Steerpike and Titus’s lethal confrontation (pp. 768-799). In an absurd vein, there’s the scene where the castle’s coterie of tutors turn their dining tables upside down and sit on them like rowers in a boat, all according to a ritual whose purpose has been lost (pp. 498-9). Equally absurd is Irma Prunesquallor’s matchmaking party (pp. 564ff); or nearly as intense as Steerpike’s fate is the young earl’s first and last meeting with The Thing (pp. 730-7).

I like Peake’s attention to detail and patience in creating a picture and setting a mood; considerations not often addressed in many fictions. I can see why some find this book tedious but it’s the rare novel where I can so vividly see what I’m reading.

And our author is as masterful in painting word images as in the first novel. Here’s his description of Professor Bellflower:

He was a fine-looking man in his way. Big of head, his brow and the bridge of his nose descended in a single line of undeniable nobility. His jaw was as long as his brow and nose together and lay exactly parallel in profile to those features. With his leonine shock of snow-white hair there was something of the major prophet about him. But his eyes were disappointing. They made no effort to bear out the promise of the other features, which would have formed the ideal setting for the kind of eye that flashes with visionary fire. Mr Bellgrove’s eyes didn’t flash at all. They were rather small, a dreary grey-green in colour, and were quite expressionless. Having seen them it was difficult not to bear a grudge against his splendid profile as something fraudulent. His teeth were both carious and uneven and were his worst feature. (p. 437)

Or, a favorite, his description of the odious Barquentine:

Barquentine in his room, sat with his withered leg drawn up to his chin. His hair, dirty as a flyblown web, hung about his face, dry and lifeless. His skin, equally filthy, with its silted fissures, its cheese-like cracks and discolorations, was dry also – an arid terrain, dead it seemed, and waterless as the moon, and yet at its centre those malignant lakes, his vile and brimming eyes. (p. 608)

Three characters stand out as my favorites:

The first is Flay, Lord Sepulchrave’s (the 76th earl) first servant. He begins the story a close-mouthed, ill-tempered man but becomes one of Titus’s fiercest protectors and close friend.

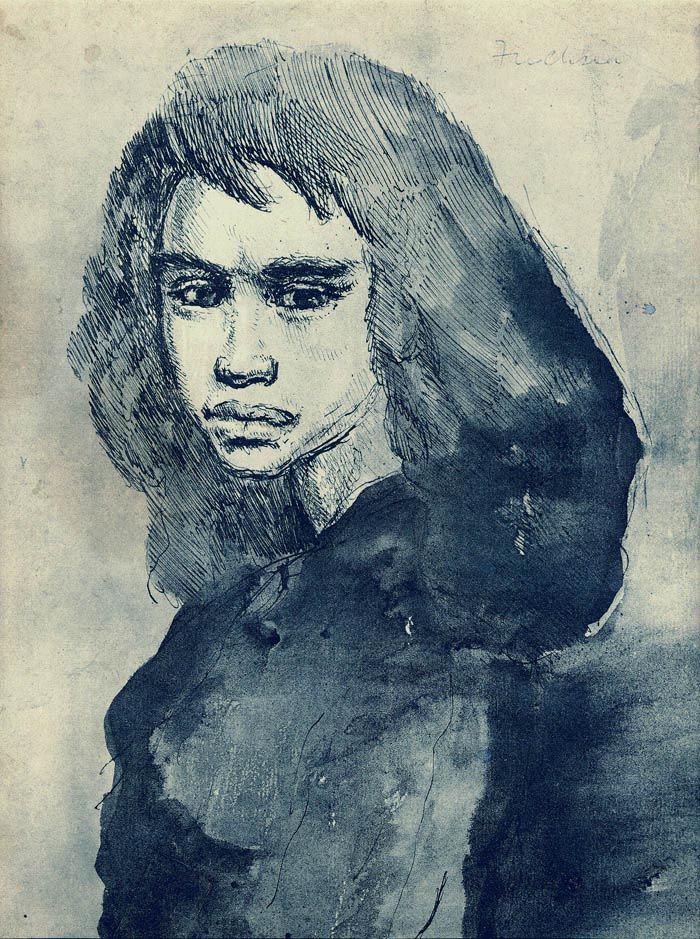

Fuchsia, Titus’s older sister, begins the books a spoiled, utterly self-centered brat but she also grows and matures into a woman whose tragic end is moving and gut wrenching.

What was the darkest of the causes for so terrible a thought it is hard to know. Her lack of love; her lack of a father or a real mother? Her loneliness. The ghastly disillusion when Steerpike was unmasked, and the horror of her having been fondled by a homicide. The growing sense of her own inferiority in everything but rank. There were many causes, any one of which might have been alone sufficient to undermine the will of tougher natures than Fuchsia’s.

And then there’s Steerpike, the adolescent kitchen slavey who rises to become the de facto master of Gormenghast. In Titus Groan, the reader can feel a certain sympathy with the youth but in Gormenghast, he assumes an evil of Miltonesque stature:

But Steerpike hardly heard him. His future was ruptured. His years of self-advancement and intricate planning were as though they had never been. A red cloud filled his head. His body shuddered with a kind of lust. It was the lust for an unbridled evil. It was the glory of knowing himself to be pitted, openly, against the big battalions. Alone, loveless, vital, diabolic – a creature for whom compromise was no longer necessary, and intrigue was a dead letter. If it was no longer possible for him to wear, one day, the legitimate crown of Gormenghast, there was still the dark and terrible domain – the subterranean labyrinth – the lairs and warrens where, monarch of darkness like Satan himself, he could wear undisputed a crown no less imperial. (p. 705)

Alas, Peake kills off all three ere Gormenghast ends.

Titus Alone: Part 3 of 3

Titus Alone is admittedly the weakest of the three novels. The glass city, the Black House, Cheeta and all the other characters who populate its pages are pale indeed to their counterparts from Titus Groan and Gormenghast. No one has the same presence or reality that even so minor a character as the Poet achieves. And it doesn’t help that – even in the first books – I have no real interest in Titus.

The strongest part of the final volume is the end, when Titus, after much wandering, finds himself standing before a recognizable landmark, knowing that over the ridge he’ll find Gormenghast, and realizes he doesn’t need to go home to find home:

His heart beat out more rapidly, for something was growing…some kind of knowledge. A thrill of the brain. A synthesis. For Titus was recognizing in a flash of retrospect that a new phase of which he was only half aware, had been reached. It was a sense of maturity, almost of fulfillment. He had no longer any need for home, for he carried his Gormenghast within him. All that he sought was jostling within himself. He had grown up. What a boy had set out to seek a man had found, found by the act of living. (p. 1022)

In an ideal world (among the myriad things that would be better), Frank Herbert would have stopped with Dune, Spock would have remained dead at the end of “The Wrath of Khan,” the universe would not have had to endure Robin Curtiss as Saavik, and Mervyn Peake would have ended the Gormenghast novels with Titus riding off into an unknown world. So I would recommend the first two books strongly. The third is interesting and, in parts, as richly imagined as anything found in Titus Groan or Gormenghast but there’s an overall lack of intensity or engagement which makes it a more cautious recommendation.